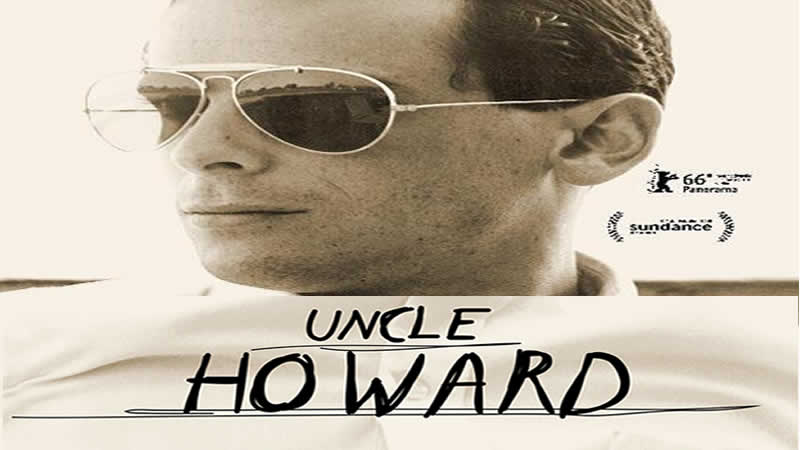

Uncle Howard Sundance Movie Review

The life and work of Howard Brookner, a rising force in independent filmmaking cut down by AIDS in 1989 at age 34, gets poignant contextualization in this portrait by his nephew.

[contentblock id=1 img=adsense.png]

In Uncle Howard, an intensely personal exhumation project with an emotional undertow that sneaks up and carries you along, director Aaron Brookner goes digging through the outtakes of a 33-year-old non-fiction feature to flesh out the ghost of his childhood hero.

The subject is the late filmmaker Howard Brookner, best known for his 1983 doc, Burroughs: The Movie. The result, however, is not just a warm portrait of one man and his small body of work; it’s also a moving journey through a largely vanished New York, a gritty place where outsider artists and creative risk-takers came to connect and grow. In that sense, the movie shares some thematic kinship with the inspiring Patti Smith memoir Just Kids, about the poet rocker’s early experiences in the city with Robert Mapplethorpe. The core years being examined here are roughly a decade later, but the snapshot of a self-nourishing Lower East Side arts scene strikes similar notes of fondness. Looking back from the present day, Aaron Brookner points to the loss of two beacons from the era as symbols of what Manhattan has become: the Chelsea Hotel and St. Vincent’s Hospital.

The Chelsea still stands but is undergoing a major upgrade, leaving behind its history of “bohemian folly,” while St. Vincent’s, where Brookner’s uncle and thousands of others were treated for AIDS-related illnesses during the crisis years, has been torn down and replaced by luxury condos. Non-fiction filmmaking in which the documentarian becomes a substantial on-camera presence can often result in the storyteller pulling focus from the subject.

[contentblock id=2 img=adsense.png]

One of the most refreshing aspects of Uncle Howard is the younger Brookner’s discreet respectfulness. Lovely home-movie footage of him as a kid shows how he gravitated toward his fun, favorite uncle, but his narration throughout retains a reserve that’s almost dispassionate. He lets the deep emotional connection surface organically.

The most important key to accessing his subject lies in “The Bunker,” as William Burroughs called his Bowery apartment. Just as the older Brookner had to get around the reclusive Burroughs’ notorious guardedness to make his film, so does his nephew have to win over John Giorno, the caretaker of the partially converted YMCA space.

[contentblock id=3 img=gcb.png]

The dusty archive contained therein is a wealth of material — outtakes, rushes, negative rolls, much of it unlogged — with lots of footage of the handsome 25-year-old Howard talking with Burroughs and other interview subjects between takes. One associate observes that “you were never on farting terms” with Burroughs, but that Brookner knew how to talk to him, so he got closer than most. (He also shared Burroughs’ heroin habit for a time.)

Terrific archive material shows Burroughs with contemporaries such as Allen Ginsberg, Andy Warhol and Lucien Carr, and Aaron Brookner bridges past and present by inviting Tom DiCillo and the eternally droll Jim Jarmusch — both of whom worked on Burroughs: The Movie early in their careers — to reflect back while poring over outtakes. Footage of other maverick artists of the time, Laurie Anderson, John Cage, Frank Zappa and Patti Smith among them, enhances the loosely structured film’s mosaic of a vibrant creative milieu. Eclectic music choices also help evoke that world. Hearing Rowland S. Howard’s lugubriously shivery vocals on “Still Burning,” for instance, suggests a punk spirit that reaches across different mediums and among multiple generations.